Lost O was programme of installations, interventions and performances by international artists, which took place in Ashford as the Tour de France passed through the town in 2007.

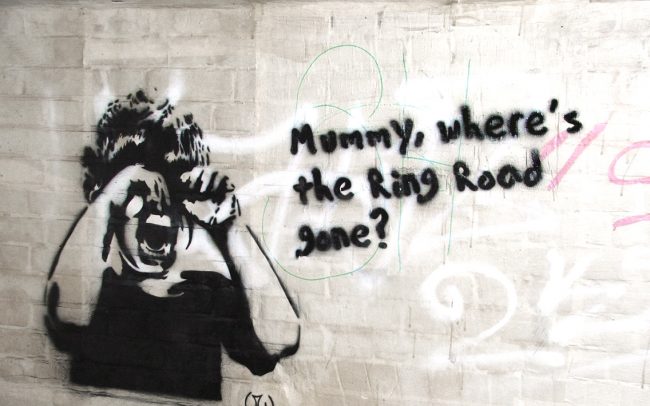

Lost O de-marked a dramatic and critical moment of change as Ashford’s four lane ring road was transformed into the largest Shared Space scheme in Europe. The fast flowing traffic on this road had isolated the centre of the town from its residential neighbourhoods. For Lost O artworks were curated that acknowledged and celebrated the loss of the ring road changing the perceptions of the town for both Ashfordians and visitors alike.

The commissioned artists were Akay, Roadsworth, Simon Faithfull, Gary Stevens, Dan Griffiths, Mark Prier, Thomson + Craighead, Brad Downey, Bryony Graham, Olivier Leroi

TAKING FLIGHT by Richard Cork

From the moment I arrive in Ashford on this memorable Tour de France Sunday, its transformation becomes spectacularly apparent. Opposite the Fat Fiddler pub, at the top of the road leading up from the train station, a spectral apparition invades my vision. The South Kent College was a much-loved local landmark, asserting its sturdy red-brick presence to visitors as they approached the town centre. But now, quite suddenly, it has vanished. The entire edifice looks bleached and ghostly, glowing in the early July light. Enormous sheets of white paper have been painstakingly applied to the surface, and they divest the building of all its former substance.

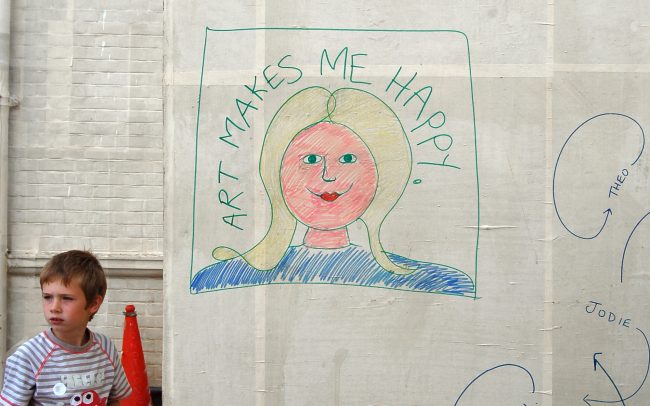

But not for long. As I get closer, a child becomes visible. Hard at work on this tempting expanse of whiteness, he is already challenging its purity by painting a comic and grotesque image called “I Am The Leg Monster.” Akay + Made, the Swedish artists responsible for papering the College, watch the boy. They show no sign of stopping him. On the contrary: as subversive agents who earned their own reputation making provocative and often illegal art in public spaces, Akay + Made fully expect their Ashford masterwork to be covered in graffiti. The College was, after all, an art school at one time. So they like the idea of rival guerrilla artists using this reborn building as an irresistible canvas for drawing and painting.

Interactivity of that freewheeling kind is welcomed by Akay + Made, even though their Ashford project required an intense amount of tough, highly focused labour. A cherrypicker was brought in to assist them, along with another artist called Michael. Yet it was still an arduous task, requiring them to endure fierce onslaughts of wind and rain in one of England’s worst summers for many years. They tell me that their work continued on site until two o’clock this morning, so I am not surprised when they confess to feeling exhausted. But Akay + Made have accomplished their ambitious task with immense professional aplomb, and describe how elated they feel to have given this whole disused structure such an arresting new life.

They are fortunate to have escaped the interfering attention of punitive officialdom. Not far from Akay + Made’s luminous tour de force, I come across a victim of our current national obsession with health and safety.

Brad Downey is a young and feisty American who thrives on an almost Situationist approach to art. He installed a work called, with his typically wry sense of humour, Long Weight. Erected at the junction of Elwick Road and Station Road, where the traffic stream of Ashford’s notorious Ringway is often frankly oppressive, Downey’s intervention mounted Puffin crossing units on four-metre columns. As a result, anyone wanting to change the lights and negotiate a path across the road had to devise some method of scaling his columns to reach the push-button controls.

It is Downey’s first-ever commission. Previously, his construction pieces have all been off-the-cuff, executed in highly unorthodox locations like the so-called Madonna and Child he made near Euston Station. Always dressed as a construction worker, Downey usually manages to carry out his work unimpeded — although he did get arrested recently in Scotland. At Ashford, however, he fell foul of Keith Ferrin, MP for Swale West and Cabinet Member for Environment, Highways & Waste. Despite passionate and indignant protests from a significant number of Downey’s supporters, Ferrin decided that this irredeemable “Art Sculpture” looked “as if Kent Highway Services had incorrectly placed apparatus required for the use of a pedestrian facility.” In an email sent to him on 5th July, I argued that Long Weight’s perverse wit deserved to be savoured, and that “Ashford should feel proud to have it.” Yet Ferrin remained adamant, insisting that “the artist’s work compromised safety.” Downey himself seems at once rueful and stoical when I meet him. “I don’t mind being taken away”, he says, admitting that “I’m used to it. But I always think about safety — you have to if you’re doing illegal stuff. It’s all about opening people’s minds, and I always try to make it positive because there’s so much negativity around.”

Mercifully, Ferrin’s intolerance did not prevent Thomson + Craighead from steering ten real sheep into the graveyard beside Ashford Parish Church. Colin Preece, the vicar of St Mary the Virgin, has a far more enlightened attitude to contemporary art. He also understands that, in the past, sheep would have been relied on to keep the grass short in this revered part of the market town. Long before I see them, their sound beguiles me. For Thomson + Craighead have attached bells to the animals’ necks, and they chime a diminished seventh cord. It hangs in the air with haunting potency, albeit competing sometimes with the Sunday ringing of St Mary’s old church bells. Consistently fascinated by music in their earlier work, Thomson + Craighead realise that the diminished seventh is often deployed in a composition’s final cadence to the tonic. It seems appropriate in a setting as sensitive as this ancient graveyard, where tombs are still legibly inscribed with sacred tributes to Ashford citizens like Richard Pattenden, who was only twenty-eight when he died in 1851 “leaving his disconsolate widow to lament her loss.”

I notice that the sheep’s bells vary considerably in sound according to the animals’ activities. When they are absorbed in eating, their bells make a higher, lighter ring. Yet when they begin dashing around in groups, displaying an instinctive herd mentality, the bells become louder and deeper. The most startling moment occurs when, without warning, one of the animals leaps on a tombstone and then launches himself into space. He appears suspended in slow motion and very graceful before, quite suddenly, landing with a clangourous clashing of bells. Another sheep quickly performs the same feat, and yet this excitement does not make all the animals follow suit. They soon lapse into motionless silence, forever glancing around anxiously as if expecting an imminent ambush. This nervousness contrasts oddly with their otherwise docile demeanour, and it makes me watch them with as much absorbed fascination as I give to the sound of their bells.

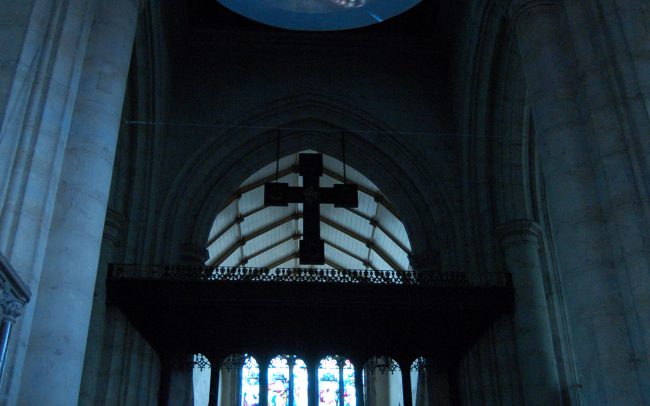

Nothing could be more removed from this experience than the work installed in the church itself. For here, gazing up into St Mary’s tower, I discover Simon Faithfull’s video Orbital No 1 defining the dynamism of urban speed today. No sounds, either of sheep bells or roaring engines, can be heard within this shadowy sanctum. Instead, silence prevails as the three concentric ovals in Faithfull’s work take me into a world of incessant motion. Projected onto a flat surface supporting the bell-chamber above, Orbital No 1 pitches me into the dizzying experience of metropolitan travel on the Circle Line of the Tube, the North and South Circular and finally, on the outside oval, the M25.

On a painterly level, the gold and amber richness in the central oval contrasts with the more monochromatic coolness of the other two journeys. But Faithfull also makes me intensely aware of the ovals as giant eyes. I seem to be looking into his head as he drives a car along the M25, rides on the back of his friend’s motorbike on the North and South Circular, and sits next to the driver of a Tube train travelling round the Circle Line. In all three journeys, the images are very immediate. Faithfull tells me that he felt anxious about rain on his lens, and yet it also adds immensely to the vivid sense of dynamism. So does his decision, in the Tube, to avoid the dirty front window by leaning out of an open door. Looking at all three videos in concert, I find that the outcome is oddly hypnotic — like a mandala galvanised into frenetic motion. Thoughts of Dante’s odyssey through heaven and hell also come to mind, especially when the innermost eye goes black. It becomes a void, with everything rushing ceaselessly around it. And viewed at St Mary’s, where outstanding Elizabethan monuments memorialise the Smythe family on nearby walls, Faithfull’s work proves that the modern world of insistent, repetitive energy deserves to be represented even in a church whose origins stretch right back to Saxon times.

After emerging from St Mary’s, all thoughts of motorised transport fade as I find myself confronting a trio of uniformed bicycle riders guarding the main entrance. Their stance turns out to be temporary: they belong to a team called La Brigade de Chambord, who are quietly patrolling the centre of Ashford and the ring road. “Sometimes people come up to us and think we’re police”, one of them admits. But the truth is that they are all actors, specially hired for a three-day Lost O performance by the French artist Olivier Leroi. The horns sprouting so bizarrely on their handlebars are real. For the Brigade began its operations in the area around Chateau de Chambord, where deer proliferate. Sporting orange caps and flamboyant pocket-flaps, the team pose coolly outside the church for a woman who photographs them with avid enthusiasm. Yet when I encounter them later, elsewhere in the town, they seem less self-consciously stylish and more matter-of-fact. Their attempts to help passers-by during this busy day appear quite genuine, and reflect Olivier’s insistence that “this is a big work they have to do and they are very serious. My brigade is peaceful, unthreatening — it’s no laughing matter.” One of his riders nods in assent, telling me: “the public can laugh, but we don’t.” He seems as solemn as the Ashford Rabbit, whom Olivier claims to have identified as the symbol of the town painted in black and gold on top of its municipal railings.

In this respect, La Brigade de Chambord is quieter and far less volcanic than the other group of figures moving through Ashford today. Gary Stevens, whose art benefits visibly from his long experience of working with live performers, has brought a group of agile young men and women into the town centre for several hours. Some are local and others from further away, but Stevens ensures that they come together as a single, coherent entity. He has trained them to behave like an amorphous constellation, half animal and half machine. Responding to instructions, they somehow succeed in filling the negative space between the objects of urbanisation. Dressed in casual summer clothes, they suddenly dart off in different directions like a starburst.

Stevens calls them Flock, and at times their bodies’ movements are weirdly reminiscent of the sheep in St Mary’s churchyard. Yet no bells accompany their performance, and the spaces they enliven are often far less emotionally loaded than a graveyard.

At one point they gather in a nondescript space, next to a shop with the word SOLD written in red on its frontage. And at other times they are a great deal more proactive than the sheep, surrounding bystanders in a menacing manner or striding around, very purposefully yet irrationally, in the middle of a pedestrian precinct. Stevens has been stimulated in his work by a diverse array of sources, ranging from the subtle understatement of Velazquez and Vermeer to the chronic excitability of the Keystone Cops. Yet somehow, Flock ends up as a single-minded and unashamedly quirky initiative, animating the thoroughfares of Ashford with its eruptive force.

Although Mark Prier likewise chooses to perform in a central outdoors location and interact with passers-by, his approach is wholly removed from Flock. Rather than indulging in shock tactics, he calmly sets up a green tent adorned with an equally green banner announcing the existence of “Nomadsland Passport Office. Open at this location. Applications available.” It is the first time Prier has taken a work outside his native Canada, where he used a variety of media and strategies to investigate subjects as dramatic as survival in the wilderness. But he seems completely at home here in Ashford High Street, sporting a dark green suit with a polished metal name-tag identifying him as Alex, the Nomadsland Passport Officer.

Sitting in a green chair with a defiantly old-fashioned Underwood typewriter on his lap (“I bought it in Toronto for twenty-five Canadian dollars”), Prier responds at once to my request for a passport. “It’s a land without a country”, he explains enthusiastically. “Pan-citizenship appeals to people, and anyone can become part of somewhere with no national boundaries.” After asking me simple questions and swiftly typing out my form, he photographs me, gives me a ceremonial hug and, while our hands are still placed on each other’s shoulders, asks me to look into his eyes and say: “Everything is going to be OK.” His friendliness is unaffected, so I am not surprised when Prier tells me that he has already done 92 passports during his week at Ashford. “The police come up sometimes, suspecting that I’ve set up a market stall without paying. But then they nod sagely and walk away: I think they might find my suit reassuring.”

Bryony Graham shares Prier’s ability to gain people’s trust. A large glass cabinet in Ashford Borough Museum, a building originally designed as the town’s Grammar School back in 1635, displays a collection of roses she made with the men and women working on the Shared Space construction. An outstanding advocate, Graham talked to all the builders and invited them to use the pure clay reclaimed from beneath the old ring road. Their inspiration lay in what she calls “the classic ceramic roses found in every trinket shop in Ashford”. The skill and delicacy of the results are immediately evident in the display case, presided over by a portrait of Sir Norton Knatchbull, the Grammar School’s dignified and hirsute founder. “They’re all very proud of their roses”, Graham tells me, “and I’m very proud of them. I know exactly who did which.”

She runs through them all, quickly naming the maker of each rose without any hesitation. I feel certain that she has been able to win round many of the road-builders to the Lost O venture. The very opposite of an alienated artist, unwilling to communicate with anyone beyond the confines of her studio, Graham encouraged everybody in the Ringway construction team to visit her Portakabin on the Elwick Road Site Compound. It became a much-visited repository for raw materials of all kinds. And outside The Oranges pub I am able to look across at this Portakabin of the Found Centre, while waiting for the Tour de France contestants to race through Ashford.

I also notice, enjoying my lager and lunch at the same spot, Dan Griffiths’ billboard-style portrait of Graham Roberts, the Consultant for the entire Breaking Boundaries scheme. Although his jacket is spattered with iconic badges, like a figure who has strayed from a trendy 1970s album cover, he also looks stern enough for an election poster. And Griffiths, who delights in fusing politics with Pop, also made sure that he placed Roberts’s portrait in front of a “Quality Used Cars” showroom. Similarly irreverent posters can be seen elsewhere in Ashford, displaying images of Councillor Neil Wallace, landscape architect Lindsey Whitelaw and road engineer Richard Stubbings. All of them are playing key roles in the town’s redevelopment, and Griffiths’ designs elevate them to a cult status. At the same time, though, he turns Whitelaw into a laughing pin-up based on Susie and the Banshees. While Stubbings, placed on a wall next to The Centrepiece Church, advances towards us like a threatening predator with both his outstretched hands ready to clutch and crush. As for the words “Kent County Council”, the sinister drips of unidentifiable liquid hanging down from them belong to the toxic nightmares of Hollywood Horror.

Two of the most powerful and resonant works can be found, appropriately, closer to the ring road. Michael Pinsky, curator of the Lost O, thrives in his art on giving subversive new meanings to objects he discovers on site. Preferring to reframe them rather than add to the world’s clutter, he has gathered a disparate collection of road signs made redundant by the Shared Space project. Duchamp’s ready-mades and Beuys’s social sculpture both lie behind the piece Pinsky has installed. At first, this memorial to the scrapped ring road occupied a patch of ground at the junction of Somerset Road and Wellesley Road. But it soon became a target for hysterical tabloid press reporters who claimed, under punning headlines like “Crash Course in Art”, that it caused minor accidents by confusing drivers. True to form, the ubiquitous Keith Ferrin from Environment, Highways and Waste promptly demanded its removal. So Pinsky’s piece was shifted back from the road to a grassland locale in front of the looming Charter House, Ashford’s largest, most obtrusive and half-empty office block. The sculpture might easily have looked crushed by this concrete hulk. Yet Pinsky has made his two concentric circles resilient enough to thrive in their new setting.

Lost O retains its deadpan strangeness intact. Uprooted from their original roadside functions, these assorted signs appear stubbornly upright and even vigilant. Their fronts still insist on warning us to “Give Way”, announce the “End of Cycle Route” and proclaim the advent of a “Cul De Sac.” But viewed from behind, they reveal metal backs as bare and purged as the most uncompromising abstract sculpture. One of them, made in Weston-Super-Mare, bears a notice insisting that “This is NOT an aluminium sign and has no scrap value whatsoever.” When I tap it, the sign emits a decidedly plastic sound. Plenty of others are, however, shamelessly metallic, and I admire the stripped simplicity of a diagonal black line scything across one white circular surface. Its clean-cut boldness compares well with the intolerably cluttered wordiness of a fussy sign announcing “P Mon-Sat 8.30am-5.30pm Permit Holders B or 4 Hours No Return Within 4 Hours.” Curiosity then impels me to walk over to the sculpture’s original roadside location. The metal sockets where Pinsky originally placed his dislocated signage are still visible there, sunk in the dried-up land. They puncture the cracked, muddy ground like a mute protest against the censorship of Keith Ferrin.

But at least he did not interfere with the work produced by Roadsworth, who is no stranger to the challenge offered by Ashford. Back in his native Montreal, Roadsworth mounted a protest against the city’s lack of cycle lanes by spray-painting them on the streets at night. That is why he did not hesitate to zero in on the ideal surface for his Lost O contribution. Taking a long stretch of tarmac, leading from Bank Street into Elwick Road, he decided to paint it with a flock of birds. The idea chimes with the title of Gary Stevens’s performance piece, not to mention Thomson + Craighead’s musical sheep. “I was inspired by the idea of the peleton”, Roadsworth tells me, using the French word for a pack of cyclists. “It goes with the herd mentality, and leaders who see an obstacle and react. They have a huge responsibility and also vulnerability, like the leaders in a cycle race.” As he speaks, a large seagull flies past us looking lost, and Roadsworth admits that “any time I enter the big-city traffic herd, I have negative feelings about it, but also a fascination with the absurdity of it all.”

Hence, no doubt, his decision to concentrate at Ashford on the parallels between cyclists and birds. When I reach the work, called Universal Synchronicity, the tightly massed Tour de France competitors have already ridden over it. In their wake, a random succession of cars, vans and lorries are driving over the yellow flock Roadsworth has painted directly on the tarmac. Although it is disconcerting to watch their tyres momentarily obliterating the birds, I soon realise that Universal Synchronicity cannot be appraised from the pavement. The birds have little visual impact unless you are prepared, somehow, to dodge the traffic and stand right in the middle of Elwick Road.

From here, they amply repay the effort and risk involved. I feel surrounded by birds, and see precisely how they swerve, in unison, from one side to the other and back again. They all seem to be copying each other — wings in, wings out, wings down. And their incessantly curving rhythms break up the rectilinearity of the road with a heady, unstoppable momentum. The painting itself terminates just before Church Road leads off to the left, but by then the birds have built up such a strong visual impetus that they appear bent on heading for the train station and on towards infinity. Like all the finest work in this audacious and unpredictable show, the birds seem to accept no limits in their determination to make our imaginations take flight.

RICHARD CORK – 2008